The Nielsen Norman Group’s State of UX 2026 opens with reassurance: “things are starting to settle.” After years of volatility—layoffs, hiring freezes, existential questions about the field’s value—the job market is “stabilizing.” NN/g frames this as positive correction: the post-COVID hiring frenzy was unsustainable, the 2023-2024 contraction was painful but necessary, and now the field is finding its proper equilibrium. Their prescription is unambiguous. To thrive in 2026, practitioners must “design deeper to differentiate,” become “adaptable generalists,” and demonstrate clear business impact. The field is not dying. It is maturing.

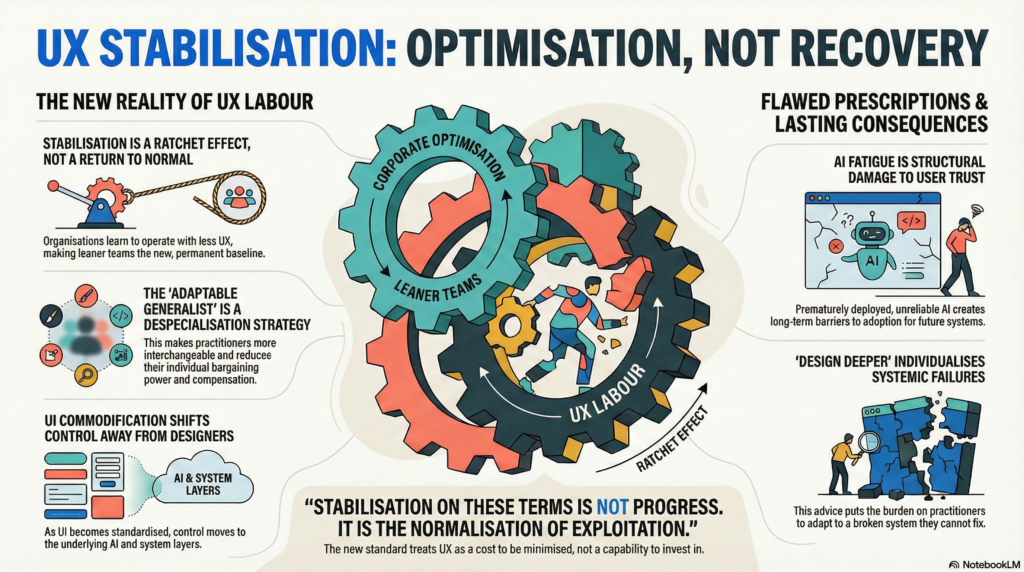

This narrative treats stabilization as the end of chaos and the return of clarity. But stabilization is not recovery. It is the completion of a reorganization—one that redefines what UX work is worth, who performs it, and where control resides. The question NN/g does not ask is: stable relative to what baseline, and optimized for whose benefit? When a market stabilizes, it has finished learning something. What organizations learned through 2023-2024 was not that UX is valuable. They learned exactly how little UX labor they need to purchase, and at what cost.

What Stabilized: Reduced Demand at Compressed Capacity

NN/g supports their stabilization claim with survey data from UXPA and User Interviews showing that “UX-related team sizes are now staying consistent, and may even grow soon.” They acknowledge the job market remains competitive, particularly at entry levels, but frame this as transitional difficulty rather than structural change. The underlying assumption is that volatility was temporary—organizations overcorrected during layoffs, and now they are finding the right sizing. Markets, in this view, self-correct toward efficiency.

But labor market “stabilization” is an operational outcome, not a neutral description. Stability relative to what baseline, optimized for whose objectives? NN/g frames 2024’s volatility as aberrant—a roller coaster that has finally leveled out. What they do not examine is whether the levels are equivalent. The post-2024 baseline is not 2021 restored. It assumes leaner teams, compressed roles, and heightened scrutiny of UX’s business contribution. Practitioners are expected to perform work previously distributed across multiple specialists while simultaneously defending the legitimacy of that work existing at all.

This is not a return to equilibrium. It is a ratchet effect. When organizations cut UX staff during budget contractions, they learned that products ship anyway—perhaps worse products, but products that meet shipping deadlines and generate revenue. When remaining practitioners absorbed additional responsibilities, organizations learned that specialization was optional luxury, not operational necessity. When practitioners were forced to justify their existence through direct business metrics, organizations learned that UX could be treated as a cost center subject to continuous optimization rather than a strategic capability requiring investment.

The operational reality NN/g describes but does not name is that stabilization means the system finished learning how little UX labor it needs to purchase, and at what cost. Team sizes staying “consistent” is not evidence of UX’s value being recognized. It is evidence that organizations found the minimum viable staffing level. Practitioners survive not by designing better products, but by becoming more efficient at producing artifacts that satisfy organizational demands for deliverables—even when those artifacts have minimal impact on the actual system behavior determining user experience. The interface gets documented; the system beneath it remains unexamined.

The Generalist Mandate: Despecialization as Labor Strategy

NN/g identifies the shift clearly: “available roles will increasingly demand breadth and judgment, not just artifacts.” They predict that “practitioners who thrive will be adaptable generalists who treat UX as strategic problem solving, rather than focusing on producing deliverables.” On the surface, this sounds like professional evolution—practitioners expanding capabilities, becoming more versatile, better equipped for complex problems. NN/g even frames it as empowering: moving beyond narrow specialization toward strategic thinking.

But generalism is not versatility. It is a despecialization strategy that makes practitioners more fungible and organizations less dependent on individual expertise. The difference is operational. When NN/g says roles will “demand breadth,” they are describing role compression: one person now performs tasks previously distributed across dedicated researchers, interaction designers, and content strategists. When they say practitioners must demonstrate “judgment, not just artifacts,” they are describing the end of artifact-based work validation. You cannot point to completed research studies or interaction specifications as evidence of value when the expectation is that you produce those artifacts while simultaneously executing strategy, stakeholder management, and business metric optimization.

The consequence of role compression is not that practitioners become more valuable. It is that they lose bargaining power. A specialist in user research or interaction design has specific knowledge that justifies specialized compensation and makes them difficult to replace. A generalist who can “do a bit of everything” is easier to reassign, easier to replace, and easier to compensate at lower levels because no single capability is considered irreplaceable. NN/g presents this as practitioners needing to “broaden their skillset,” but what organizations are doing is broadening the scope of work expected for the same—or lower—compensation.

The operational pattern is that practitioners spend less time developing deep expertise in any domain and more time performing whatever task is currently urgent. This does not produce better design outcomes. It produces practitioners who can quickly generate artifacts that look like research, look like strategy, look like design—without the depth required for those artifacts to actually change system behavior. Organizations accept this tradeoff because what they are optimizing for is not quality but throughput: the ability to claim design work happened, regardless of impact.

What NN/g frames as professional maturity—moving beyond deliverables to judgment and strategy—is actually the elimination of the structures that made specialized expertise legible and compensable. When your value cannot be demonstrated through artifacts, it must be proven through continuous performance of business impact. But business impact in resource-constrained organizations is measured by efficiency, velocity, and shipping cadence, not by the systemic improvements that prevent long-term failure. The practitioners who “thrive” under these conditions are those who optimize for organizational legibility, not for actual design quality.

UI Commodification and the Migration of Control

NN/g states directly: “UI is still important, but it’ll gradually become less of a differentiator.” They cite two converging trends. First, standardization: “Design systems, patterns, tokens, and components ensure consistency while improving efficiency. (Nobody needs to redesign the same button 300 times.)” Second, mediation: “More interactions are mediated, particularly by AI. In many products, people are spending less time navigating the UI and more time delegating to a layer sitting on top of it.”

Their analysis correctly identifies the technical trend but misreads its implications. They treat UI commodification as efficiency gain—freeing practitioners from repetitive interface work to focus on “higher-value strategic work.” But commodification is not just about cost reduction. It is about control migration and power redistribution.

When interfaces standardize, two things happen simultaneously. First, the perceived value of interface design labor decreases. If anyone can assemble competent UI from existing patterns—and increasingly, if AI tools can generate acceptable interfaces from component libraries—then the skill ceases to command specialized compensation. NN/g acknowledges this: “If you’re just slapping together components from a design system, you’re already replaceable by AI.” But they frame this as individual failure (not designing deeply enough) rather than structural devaluation of interface craft.

Second, and more critically, control migrates from the interface to the systems mediating access to it. When NN/g describes interactions as “mediated” by AI assistants, search agents, and recommendation engines, they are describing a fundamental restructuring of where agency resides. Users no longer navigate interfaces directly—they instruct intermediaries to navigate on their behalf. The interface becomes a rendering surface for system decisions rather than a space where users exercise direct judgment.

This is not a superficial change in interaction patterns. It is a shift in who controls information access, task execution, and decision framing. When users interact directly with interfaces, they retain control over navigation paths, information prioritization, and decision timing. When interactions are mediated, control transfers to whoever designs the mediation layer: its optimization goals, filtering criteria, and behavioral nudges. NN/g recognizes that “the ‘experience’ isn’t just the screen,” but they do not examine what it means when the experience is increasingly determined by systems users cannot see, understand, or meaningfully control.

The strategic consequence is that practitioners focused on interface design are increasingly working at the wrong layer. The interface is where systemic decisions become visible, but it is not where those decisions are made. Organizations that treat UX as synonymous with UI—and NN/g implicitly accepts this conflation even while cautioning against it—optimize for surface-level consistency while ignoring the structural problems determining whether systems serve users or exploit them. When NN/g advises practitioners to “design deeper,” they are asking them to address systemic problems while granting authority only over the interface layer where those problems can be documented but not solved.

AI Fatigue as Cumulative Damage to Trust Infrastructure

NN/g predicts 2026 will be “the year of AI fatigue.” They describe exhaustion on multiple fronts: practitioners tired of replacement threats, users tired of “AI slop,” organizations confronting operational costs beyond compute. Their prescription follows logically: “The winners will treat AI as a tool that recedes into the background, not as a one-size-fits-all solution.” Build trust through “fundamentals: transparency, control, consistency, and support when the system fails.” Deploy AI thoughtfully, not ubiquitously.

This advice is not wrong. But framing AI fatigue as correctable through better implementation assumes that fatigue is temporary exhaustion rather than cumulative structural damage. Trust is not an attitude that resets when better products arrive. It is a calibration system that develops through repeated interaction and degrades through repeated failure. NN/g recognizes that “trust will be a major design problem” and that “people who’ve been burned by AI features are more hesitant to adopt new ones.” What they do not examine is the operational mechanics of how trust degradation compounds over time and across organizational boundaries.

AI systems require trust calibration to function: users must learn when to trust system outputs and when to verify independently. This calibration develops through experience—users observe when AI succeeds and when it fails, gradually building accurate mental models of reliability boundaries. When AI features are deployed prematurely, optimized for engagement over reliability, or marketed with inflated capability claims, they systematically miscalibrate user trust. Early adopters learn that AI outputs are unreliable in contexts where reliability matters. Late adopters inherit this skepticism without the experience that would let them distinguish useful applications from harmful ones.

NN/g acknowledges that “AI slop” is now “ubiquitous” and that AI features have become “noise, not novelty.” But the consequence is not just diminished enthusiasm. It is defensive adaptation. Users who have been burned develop protective strategies: they ignore AI suggestions, refuse to adopt AI features, or limit AI use to low-stakes contexts where failures do not matter. This is not irrational behavior. It is learned response to systems that have demonstrated unreliability.

The structural problem is that once trust degrades at scale, recovery is not automatic. Organizations cannot deploy better AI implementations and expect users to forget prior failures. The operational reality is that AI fatigue concentrates remaining trust in organizations that never broke it, while creating barriers to adoption for any organization attempting to deploy AI features—even legitimately useful ones—after trust has been systematically damaged. The longer organizations chase AI hype without addressing reliability and UX fundamentals, the deeper the structural damage becomes. When NN/g advises building trust through transparency and control, they are describing how to avoid breaking trust, not how to repair it once broken at population scale.

“Design Deeper” as Individualization of Systemic Problems

NN/g’s central recommendation is unambiguous: “The companies and practitioners who will thrive in this era will be the deep thinkers.” They specify what this means: “wide set of tools in their toolbox,” “deep understanding of the complex goals of their work,” and above all, “adaptability, strategy, and discernment” rather than “shallowly going through the motions or templates.” Successful practitioners will “understand that our work is not just adding sparkle icons or making things pretty. It’s about deeply understanding user problems and strategically solving them to achieve business goals.”

This advice is not wrong. Deeper thinking and strategic capability are valuable. But the recommendation frames professional survival as an individual adaptation problem rather than a systemic exploitation problem. NN/g treats the challenges facing UX—job scarcity, role compression, business scrutiny, AI displacement—as obstacles individual practitioners can overcome through skill development. The implicit model is meritocratic: the field is stabilizing, opportunities exist, and practitioners who invest in the right capabilities will thrive.

What this model does not examine is what happens when organizations systematically devalue UX work while simultaneously demanding that remaining practitioners “design deeper.” When organizations cut teams, compress roles, and demand proof of business impact while withholding authority to make business-level decisions, telling practitioners to adapt is not empowering guidance. It is transferring responsibility for navigating organizational dysfunction to the individuals least equipped to change it.

The operational pattern is familiar across professional fields under resource pressure: when systemic problems exist, organizations individualize the solutions. If practitioners cannot get jobs, they need better portfolios. If UX work is undervalued, practitioners must demonstrate clearer business metrics. If AI threatens design labor, practitioners must learn new tools. The responsibility for navigating broken systems transfers to individuals who did not create the problems and cannot solve them through individual action.

This is not to say practitioners should not develop capabilities or think strategically. But the prescription to “design deeper” must be understood for what it actually is: not a solution to problems facing UX as a field, but a survival strategy within a system that has already decided how much UX labor it wants to purchase and at what cost. NN/g says practitioners who “design deeper” will “thrive.” What they do not say is that thriving looks like performing the work of multiple former specialists for compensation that reflects neither the expanded scope nor the strategic value supposedly being delivered. Practitioners who succeed by designing deeper do not change the system. They become the exceptions that prove the system works, while the majority who cannot meet escalating requirements are quietly filtered out.

What Stabilizes When Markets Stabilize

NN/g describes a field “finding its footing” after disruption. Job markets are recovering. Roles are clarifying. The path forward “feels clearer.” Their assessment is technically accurate. What has stabilized is not a temporary disruption, but the permanent recalibration of how much UX labor organizations are willing to purchase and what they expect it to deliver.

The field that stabilized is not the field that existed before 2023. It is a field where fewer practitioners do more work, where specialization is replaced by fungible generalism, where interface craft matters less than organizational legibility, where trust in AI systems degrades faster than it can be rebuilt, and where professional survival requires continuous individual optimization to compensate for systematic institutional disinvestment. This is what markets mean when they stabilize: they find the point where supply meets demand at the price organizations are willing to pay. That point is lower than it was.

NN/g’s guidance—design deeper, develop broader skills, demonstrate business impact—is the vocabulary of individual adaptation to structural decline. It assumes that if practitioners just become valuable enough, organizations will recognize that value and compensate it appropriately. But organizations already decided what UX is worth. They learned that products ship without adequate UX research. They learned that interfaces standardize without specialized craft. They learned that business metrics can justify eliminating roles faster than practitioner expertise can justify preserving them. The system stabilized because organizations finished learning these lessons.

The consequence is not that UX disappears. It is that UX becomes what it can be performed as: artifact production, component assembly, stakeholder theatre. The work that requires authority to change systems—the work that identifies and prevents systematic user harm, that questions business models built on manipulation, that insists users retain meaningful control—is precisely the work that organizations learned they can function without purchasing. When control migrates from interfaces to mediation systems, when AI agents make decisions users cannot inspect, when personalization becomes behavioral management, the practitioners with authority over interfaces but not systems can document these problems but cannot solve them.

What actually stabilized is this: the separation of UX work from UX authority. Practitioners retained responsibility for user experience while losing the institutional position required to determine it. Organizations stabilized at the point where they could extract UX labor without granting UX power. The interface may stabilize, but the system—both the technical system mediating user interaction and the organizational system determining what gets built and how—remains optimized for goals that have nothing to do with user welfare and everything to do with the efficient extraction of value from attention, behavior, and dependence.

This is what it means when NN/g says things are “starting to settle.” They are settling into their permanent configuration. The question practitioners must answer is not how to thrive within this configuration, but whether stabilization at this level is acceptable at all.