The job didn’t disappear. It got promoted.

AI agents were supposed to take work away from users. Orchestration UI gives it back, repackaged as “management.” Users moved from doing tasks to supervising the systems that do them. The cognitive load shifted, not reduced. And the interface was redesigned to make that shift look like progress.

What Agent Orchestration UI Proposes

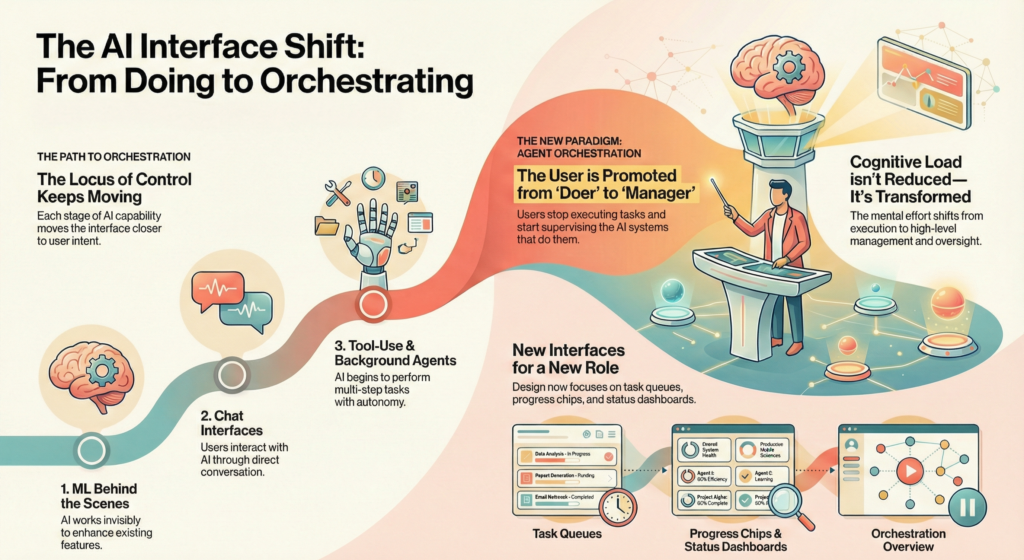

Agent Orchestration UI is an emerging design concept addressing the next interaction paradigm. As AI agents handle multi-step tasks with increasing autonomy, users need new interfaces to govern them. Task queues. Progress chips. Status dashboards. Undo checkpoints. The interaction layer isn’t disappearing — it’s transforming. Users stop executing and start orchestrating.

This sits at the frontier of a progression the AI product industry has followed over the past several years: ML behind the scenes → chat interfaces → retrieval-augmented products → tool-use agents → background agents → agent-to-agent ecosystems. Each stage adds capability. Each stage moves the interface closer to user intent and further from direct user interaction with the system.

The core design shift is stated plainly across the field: the locus of control keeps moving. Early ML features needed micro-copy. Chat demanded conversation design. Agents now need orchestration UI. The progression is presented as a natural evolution. The implication is that orchestration UI is simply the next design challenge — harder, yes, but fundamentally continuous with what came before.

It is not continuous. Something structurally different happens at the orchestration stage. And the proposal, for all its precision about capability, does not name it.

What the Progression Actually Transfers

The progression tracks what systems gain at each transition. The missing dimension is what users surrender.

At Stage 1 (ML behind the scenes), users interact with traditional interfaces. The AI is invisible. They retain direct control over navigation, decisions, and information access — even if the system subtly shapes what they see.

At Stage 2 (chat), users delegate intent through language. They lose step-by-step control but can correct course through follow-up instructions. Authority remains nominally with the user because the system waits for input before acting.

At Stage 4 (tool-use agents), systems chain actions without per-step approval. Users can steer mid-flow, but the system has already committed to a path. Corrections arrive after intermediate actions have executed. Authority becomes reactive rather than preventive.

At Stage 5 (background agents), multiple workflows run “mostly unattended.” That word “mostly” is doing critical work. It implies supervision. But supervision of what, exactly? Users see a dashboard. They see task cards with status indicators. They see whether something succeeded or failed. They do not see why the system made the decisions it made, what alternatives it considered, or what it will do next if current conditions shift.

Each stage transfers execution to the system while the interface signals that authority remains with the user. The gap between these two realities widens at every transition. Orchestration UI is the interface layer built to span that gap. Not to close it.

Monitoring Is Not Control

The proposal identifies a principle that runs through the agentic stages: trust shifts from outputs to process. In agentic stages, users trust systems more when they can see how decisions were made, not just what decisions were produced. This is true.

But it stops one step short of the structural problem. Seeing a process is not the same as controlling it.

A dashboard that surfaces task progress, agent status, and completion rates is a monitoring surface. It tells users what happened. It does not prevent what shouldn’t happen. The distinction is precise, and it is consequential. Monitoring is retrospective. Control is prospective. They are not the same cognitive operation, and they do not produce the same relationship between user and system.

The book draws this line directly in its treatment of agentic systems: “Nominal versus practical control. Humans are nominally ‘in control’ when there’s an oversight interface. They’re practically disengaged when that interface doesn’t effectively support intervention or when the system operates too quickly or opaquely for humans to meaningfully oversee.”

Orchestration UI satisfies the nominal condition. It provides dashboards, progress indicators, pause buttons, and jump-in affordances. Whether it satisfies the practical condition depends entirely on one variable: whether the system’s decision timeline is slower than the user’s reaction time. For routine, low-stakes agent actions, it often is. For the decisions that actually matter — irreversible actions, external system interactions, resource commitments — the system has usually already acted by the time the dashboard reflects it.

The Authority Illusion

This is where the pattern becomes structurally dangerous.

When an interface signals authority — through dashboards, controls, status chips, and undo affordances — users develop a mental model that they are governing the system. This mental model is accurate for low-stakes actions. It becomes inaccurate precisely at the moments when governance matters most.

The gap between what the interface implies about user control and what the system actually permits is what we can call the Authority Illusion — the agentic equivalent of what the book identifies as “Confidence Theater” in prediction systems.

Confidence Theater presents accuracy signals that don’t reflect actual system reliability. The Authority Illusion presents control signals that don’t reflect actual user influence. Both miscalibrate user judgment in the same structural direction. Both concentrate harm on users who lack independent means to verify the signals they’re receiving. Both are not implementation failure. They are properties of interfaces designed to represent a relationship that the underlying system does not actually support.

The mechanism operates in three steps. First, orchestration UI presents a coherent control surface: task queues, status chips, pause/resume/rollback buttons. Users internalize this as I am managing this system. Second, the system executes decisions faster than users review them — because the value proposition of agents is throughput, and throughput and meaningful human oversight are structurally opposed for consequential actions. Third, when something goes wrong, the dashboard shows what happened. But the user’s ability to prevent it was never there. The control interface documented the outcome. It did not enable the intervention.

This is not a failure of design quality. It is a structural condition of systems designed to operate faster than humans can meaningfully oversee them.

What Agent Dashboards Actually Show

The proposal specifies what orchestration interfaces need: task cards with status and cost, “jump-in” affordances, and progressive autonomy tiers. Pause, resume, rollback. Confidence signals. Provenance indicators.

These are genuine design problems. They need to be solved. But none of them address the question that determines whether orchestration UI is control or decoration: At what point in the agent’s decision chain does the user’s intervention actually change the outcome?

A pause button is meaningful if the task can be paused without consequence. It signals control without enabling it if the agent has already contacted external systems, committed resources, or triggered downstream actions that cannot be undone. A rollback button is meaningful if the action is reversible. It is an aesthetic element of the interface if the real-world state has already changed.

The book identifies this gap directly: “‘Pause’ and ‘stop’ are not sufficient controls. They’re binary, and they abandon context. Users need controls that let them redirect, not just halt.”

But redirection requires understanding what the system was doing and why, which requires transparency into decision processes that multi-agent architectures make increasingly difficult to provide. When agents coordinate with other agents, when context is assembled and discarded across steps, when decisions compound through sequential and parallel pipelines, the decision chain becomes emergent. No dashboard can fully represent emergent behavior. What the orchestration UI shows is a simplified model of the process. The process itself remains structurally opaque.

The Uncomfortable Architecture

The six-stage progression underlying Agent Orchestration UI is presented as the natural evolution of AI products. Each stage adds capability. Each stage is framed as progress toward less friction, more alignment with user intent, and fewer steps between goal and outcome.

But each stage also represents an organizational decision to grant systems more autonomy, a decision driven by throughput optimization, not user benefit. And each stage exports the resulting complexity to a new interface layer while maintaining the implicit claim that users retain meaningful control over what happens.

The authority deficit accumulated across these stages is not a bug in the progression. It is the point of it. Systems that operate faster than human oversight are more productive than systems that don’t. Organizations want that productivity. Orchestration UI is the interface designed to make the productivity gain feel like it comes with governance attached.

It does not. The governance is cosmetic. The productivity is real. And the users who internalize the dashboard’s signals of authority — who believe they are managing, not merely watching – will not discover the difference until something goes wrong that they were shown but could never have prevented.

That is not a design problem to be solved with better patterns or more transparent dashboards. It is a structural condition of delegated systems where delegation speed exceeds oversight capacity. Orchestration UI does not resolve this condition. It makes it bearable to look at.